Cochlear Implant

A cochlear implant is an electronic device that restores partial hearing to individuals with severe to profound hearing loss who do not benefit from a conventional hearing aid. It is surgically implanted in the inner ear and activated by a device worn outside the ear.

In most cases, the hair cells are damaged and do not function. Although many auditory nerve fibres may be intact and can transmit electrical impulses to the brain, these nerve fibres are unresponsive because of hair cell damage. Since severe sensorineural hearing loss cannot be corrected with medicine, it can be treated only with a cochlear implant. Cochlear implants bypass damaged hair cells and convert speech and environmental sounds into electrical signals and send these signals to the hearing nerve.

The microphone captures sound, allowing the speech processor to translate it into distinctive electrical signals. These signals or “codes” travel up a thin cable to the headpiece and are transmitted across the skin via radio waves to the implanted electrodes in the cochlea. The electrodes’ signals stimulate the auditory nerve fibres to send information to the brain, where it is interpreted as meaningful sound.

The implant team (otolaryngologist, audiologist, nurse, and others) will determine your candidacy for a cochlear implant and review what you may expect as a result of the cochlear implant.

Cochlear Implant Surgery

Cochlear implant surgery is usually performed under general anaesthesia. An incision is made behind the ear to open the mastoid bone leading to the middle ear space. Once the middle ear space is exposed, an opening is made in the cochlea and the implant electrodes are inserted. The electronic device at the base of the electrode array is then placed under the skin behind the ear.

Three to Four weeks after surgery, cochlear implant team places the signal processor, microphone, and implant transmitter outside your ear and adjusts them. They teach you how to look after the system and how to listen to sound through the implant. There are many causes of hearing loss and some patients may take longer to fit and require more training due to individual differences. Your team will ask you to come back to the clinic for regular checkups and readjustment of the speech processor as needed. While cochlear implants do not restore normal hearing, and benefits vary from one individual to another, most users find that cochlear implants help them communicate better through improved lip-reading.

Perforations do not always heal with medical management alone. Thus, in some cases, microsurgery may be necessary to close the perforation. This surgery is called tympanoplasty.

Long-standing perforations can be more severe due to infection and erosion of the bones of hearing, which disrupt the bony chain of the middle ear. An audiogram (hearing test) is taken to determine the degree of hearing loss. If the hearing loss is mild and hearing improves upon patching of the hole, then almost certainly the bones of hearing (ossicular chain) are intact. Thus, reconstruction of the eardrum will be a curative procedure.

However, when there is a larger hearing loss, there is very likely to be damage to the bones of hearing. There is no way to determine the status of the bones of hearing preoperatively in this situation.

Very active infection which does not dry up with standard techniques may indicate that there is an infection in the mastoid bone. The mastoid bone is the hard bone that you feel if you press behind your ear. Within this bone, there is an air-filled space called the mastoid cavity. This air-filled space connects with the middle ear which is also air filled. Infections of the middle ear can spread into the mastoid cavity causing a more serious infection called mastoiditis. A CT scan may be necessary to evaluate this possibility further.

Surgery to reconstruct the tympanic membrane (eardrum) can be performed under general anaesthesia. The operating microscope helps to enlarge the view of the ear structures, giving a more detailed image to the ear surgeon. It is performed by an incision behind the ear.

This elevates the entire outer ear forward, gaining access to the perforation. Once the hole is exposed fully, the perforated remnant is rotated forward, and the bones of hearing are inspected. There may be scar tissue and bands surrounding the bones of hearing. These can be removed with micro hooks.

Having identified the bones of hearing, the ossicular chain is pressed to determine if the chain is mobile and functioning. If the chain is mobile, then the remaining surgery concentrates on repairing the drum defect.

A tissue is taken either from the back of the ear or from the small cartilaginous lobe of skin in front the ear called the tragus. The tissues are thinned and dried. An absorbable gelatin sponge is placed under the drum to allow for support of the graft. The graft is then inserted underneath the remaining drum remnant and the drum remnant is folded back onto the perforation to provide closure. Absorbable packing is done to fill the ear canal above the graft. Sterile packing is done to cover the rest of the ear canal.

The ear is then stitched together. A sterile dressing is done to cover the ear.

After about ten days, the packing and stitches are removed and a good evaluation can then be obtained as to whether the graft was successful. Water is kept away from the ear and blowing of the nose is discouraged. If there are allergies or cold, further antibiotics and decongestant should be given.

In over 90% of cases, the tympanoplasty procedure is successful and a hearing test is performed at four to six weeks after the operation.

If the bones of hearing are eroded, then ossicular reconstruction (reconstruction of the bones of hearing) may be necessary at the time of tympanoplasty. In some cases, this can be determined before the surgery. In other cases, it only becomes obvious at the time that the ear is completely opened and examined under the microscope.

Selection and Results

Tympanoplasty surgery is not always recommended. Chronic sinus or nasal problems such as severe allergies make the operation more difficult. They must be cleared up or controlled prior to tympanoplasty surgery.The ear and nose are connected by the eustachian tube. If there is an active infection in the sinuses or nose, infected materials may block the eustachian tube or even back up into the tube itself. Severe allergies may cause swelling of the tube which is normally lined with mucous membranes. Unless allergies are controlled, the swelling will block the eustachian tube and surgical attempts to repair the eardrum will fail.

If most of the eardrum is absent and the ossicles are destroyed by prior infection or disease, reconstruction will have to be staged into several operations. The first-stage operation reconstructs the eardrum. The second-stage operation, performed six months to one year later, addresses the reconstruction of the bones of hearing.

Mastoid infection, if present, may require that tympanoplasty surgery include mastoidectomy. The mastoid cavity may contain a reservoir of infection. If this material is not cleaned out, the new eardrum will break down after initial success. Thus, it is advisable to obtain a CT scan to visualize the mastoid cavity, if there is a history of prolonged and resistant infection. If the mastoid cavity appears diseased, the tympanoplasty with combined mastoidectomy is often recommended. This operation, termed tympanomastoidectomy, not only involves repairing the eardrum but during the same operation, the mastoid bone is opened with a drill and all diseased tissue is removed. This procedure may lengthen the operation by 45 minutes or more, but it will improve the chance of a successful result.

- A cholesteatoma is a smelly, white mass of skin scales and debris in the middle ear. It can cause hearing loss and extensive destruction of bones. The surgery done to cure cholesteatoma is called mastoidectomy.

- The majority of cholesteatomas, especially in adults, are acquired. They are a result of severe infections from perforations of the eardrum or are the result of chronic middle ear problems.

- Also, the eardrum can be progressively pulled down and retracted into the middle ear space. The skin of the ear drum then grows inside the middle ear and mastoid to form a cholesteatoma. Less commonly, cholesteatomas may form congenitally

- Cholesteatomas, when small, can often be removed without separating the bones of hearing. Larger cholesteatomas may require extensive surgery. Large cholesteatomas can be very deep in the inner ear. These usually present extensive hearing loss and facial weakness on the side of the cholesteatoma.

- As acquired or congenital cholesteatomas increase in size, they can also affect the nerve that moves the face, the facial nerve. This nerve extends from the brain to the face by going through the inner ear, the middle ear, exiting near the forward tip of the mastoid bone, rising up to the front of the ear, and finally branching into the upper and lower face. Infected cholesteatomas may erode the bone covering this nerve. Pressure or irritation by the cholesteatoma on the facial nerve may then result in facial weakness or actual paralysis of the face on the side of the involved ear. In this case ear surgery may be necessary on an emergency basis to prevent permanent facial paralysis.

- In more extensive cholesteatomas, the tumour may have eroded through the bony wall which separates the middle ear from the mastoid. This may require a more radical operation, removing the wall separating the middle ear from the mastoid.

- In congenital cholesteatomas, the eardrum is intact and there is no infection present, so the surgery can be performed more quickly.

- Hearing reconstruction is often delayed because it is necessary to rebuild the bones of hearing at a future date.

- With an intact canal wall, rebuilding the bones of hearing is delayed for a year after the primary operation for cholesteatoma. The eardrum is opened at the second operation and the bones of hearing are then reconstructed.

- Most cholesteatomas require that an incision is made behind the ear to expose the disease adequately. The cholesteatoma is completely removed microscopically

- Even with the careful microscopic surgical removal of cholesteatoma, 10% to 20% of cholesteatomas can recur. Thus, careful follow-up visits must be planned, in order to identify regrowth early on.

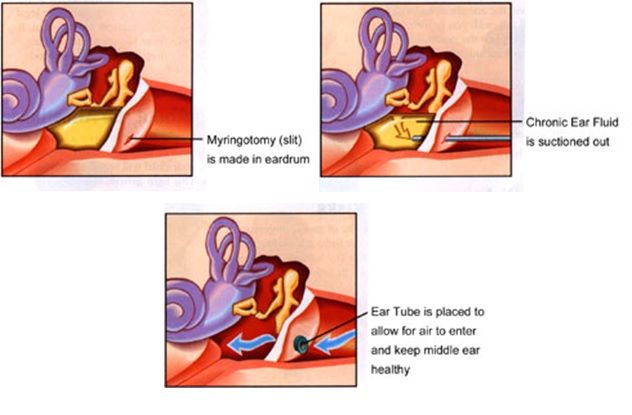

After the specialist confirms that fluid is present behind both eardrums, further medical treatment is often advised. If the fluid has been present for over 12 weeks, surgical drainage of the fluid is often indicated.

The decision to perform surgery should be based on the response to medical treatment, the degree of hearing loss and the appearance of the eardrum itself under the surgical microscope.

Surgery which drains fluid involves a small incision in the eardrum so that the fluid can be gently removed and a tube can be inserted.

The procedure medically termed a myringotomy and tubes, or tympanostomy and tubes are performed on children under general anaesthesia. Surgery is performed on an ambulatory or same-day surgery basis.

Parents often ask why the fluid cannot be drained without inserting a tube. The need for the tube insertion is because the eardrum incision generally heals very rapidly. As soon as the eardrum heals, fluid will re-accumulate. Tubes were first introduced because of this very problem. Most tubes will gradually be rejected by the ear and work their way out of the eardrum. As they come out, the eardrum seals behind the tube. Tubes will last four to six months in the eardrum before they come out. Occasionally, the eardrum does not heal completely when the tube comes out.

The majority of children treated with tubes do not require further surgery. They may have ear infections in the future, but most will clear up with medical treatment. Some children are very prone to ear infections and have a tendency to accumulate fluid after each infection.

In addition to the insertion of a tube, a careful search for underlying causes of Eustachian tube function should be sought, particularly in a child who has recurrent infections and requires a second set of tubes.

Ossicular chain is the small bones of the middle ear which are articulated to form a chain for the transmission of sound from the tympanic membrane to the oval window. In its early stages, cholesteatoma tends to attack the ossicles, the small bones conducting sound from the eardrum to the inner ear. Due to the erosion of the ossicles, there is a discontinuity of the ossicular chain and sound waves cannot transmit to the inner ear, as a result, hearing loss develops.

Ossiculoplasty is defined as the reconstruction of the ossicular chain. The ideal prosthesis for ossicular reconstruction should be biocompatible, stable, safe, easily insertable, and capable of yielding optimal sound transmission.

The most commonly used autograft material has been the incus body, which is often reshaped to fit between the manubrium of the malleus and the stapes capitulum. Alloplastic materials can also be used for ossicular reconstruction today. Alloplastic materials can be classified as biocompatible, bioinert, or bioactive such as polyethylene tubing, Teflon, and Proplast are used.

Conductive hearing loss from ossicular chain abnormalities may result from either discontinuity or fixation of the ossicular chain. In order of frequency, discontinuity most commonly occurs because of an eroded incudostapedial joint (occurring in approximately 80% of patients with ossicular discontinuity), an absent incus, or an absent incus and stapes superstructure. Ossicular fixation, exclusive of otosclerosis, most commonly occurs from malleus head ankylosis or from ossicular tympanosclerosis.

The status of the ossicular remnants determines which implant can be used. In general, better hearing results are achieved when as much of the remaining functional ossicular chain as possible is used during reconstruction.

A PORP (partial ossicular replacement prosthesis) is the best option for ossicular reconstruction when the malleus and incus are absent in the presence of an intact stapes.

A TORP (total ossicular replacement prosthesis) is the best option for reconstruction when the only footplate is present.

The operation is commonly called a stapedectomy or more correctly a stapedotomy. This operation has traditionally been carried out under a local anaesthesia.

Using an operating microscope the surgeon lifts up the eardrum. Often a small amount of bone needs to be scraped away to get a clear view. At this stage, it is important to confirm the diagnosis and check that it is otosclerosis that is causing the problem. Using delicate instruments the upper part of the stapes can then be removed. In order to re-establish the chain for transmission of the sound waves, a small hole is made in the remaining part of the stapes (the footplate).

A tiny piston is then inserted into the hole and attached to the second bone in the hearing chain (the incus). The vibrations from the eardrum can now be transmitted again to the inner ear. At the end of the operation, a thin ribbon-like pack is placed in the ear canal and left for two weeks.

It is quite common to feel a little dizzy after the operation. Dizziness is usually elicited by rapid head movements and so it is advisable to rest and avoid strenuous activity. It is also worth avoiding anything that might increase pressure in the head like straining or heavy lifting. If you need to sneeze try to do so through your mouth to minimize the pressure effect on the ear. It is customary to stay off work for a couple of weeks although this will depend upon the nature of your work. During this time the hearing is likely to be muffled due to the packing in the ear. After two weeks the packing is removed from the ear. However, it usually takes several weeks for the hearing to settle completely and there are often fluctuations in hearing over the first few weeks.

In general, the operation is very successful with over 90% of people experiencing a good improvement in hearing. Sometimes the hearing remains unchanged and there is a small (approx 1-2%) chance of hearing loss. Dizziness, which is experienced by most patients for a short time after the operation, may persist and become troublesome but again this is a rare complication. The nerve that supplies the taste buds at the front of the tongue can be damaged. Usually, this is only temporary but occasionally the nerve will have to be cut and a permanent loss results. The nerve that moves the face is located very near to where the surgery is taking place but it is extremely rare for this to be damaged. Sometimes the nerve may be abnormally sited and this may mean that it is not possible to complete the operation.